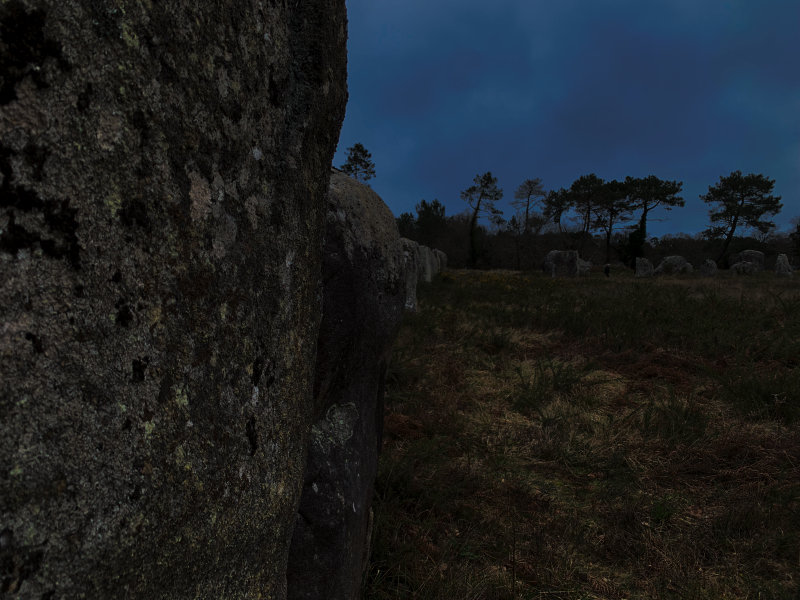

Carnac, in the south of Brittany, is home to one of the largest collections of neolithic standing stone assemblages in the world. Spread over four kilometres, these three thousand or so stones–almost all aligned east to west, from smallest to largest–were erected between 8,000 and 5,000 years ago.

Their meaning, purpose, methodologies of selection, shaping, and installation, are all completely unknown.

There are serious and responsible theories for all of this. Serious and responsible arguments for all of this.

But we simply don’t know.

And never will.

How wondrously magnificent is that? As we sit–according to some–on the precipice of the merging of human and machine intelligence in its differing (and perhaps incompatible) expressions; at a place in our intellectual evolution where we can recreate stars, where the things that can kill us are vanishing, where we feel we can ignore those that remain because of our surety that in time we will overcome them as well, there are monuments, human-made monuments, to our contemporary and future ignorance.

This is an extraordinary condition in a time of hyperknowledge.

This, and mostly only this, was at the forefront of a trip last week back to Carnac. I’d last been nearly 50 years ago (a realisation that made me gasp when I did the math, but which is nothing alongside these stones, who have seen hundreds of human generations rise and fall around them). It was time for a little getaway, and so a friend and I took a road trip, stopping along the way at a few considerably younger sites of medieval and early modern efforts at stamping mind on stone and place.

It’s possible, and if one considers sites like England’s Stonehenge (a similar mystery) perhaps even likely, to feel that you’re in the presence of something mysterious, something transcendental, perhaps even alien. And, it is true, that stones like these, and sites of deep, deep history scattered in landscapes around the world, are perhaps the closest thing we have to alien contact. They are of us, but an us–that aside from a Darwinian understanding of structural evolution–is utterly other.

I watched a middle-aged woman from Germany walk amongst the stones, trailing her fingers across the rough grey white granite and polychromatic lichen, that along with bright yellow flowers of the omnipresent gorse, offers a color field and tactility perhaps unchanged for the last eight millennia. Seeing and feeling out of time. It had been 35 years since last she had visited, and all she could do was smile and shake her head at it all. Mirroring me.

France offers so much that is part of a shared cultural experience for almost all of us moderns, that finding human places of wild incomprehension, where imagination is as reliable as knowledge, is a gift. It’s not unique, of course, to here, but it is here in abundance.

Be the first to reply